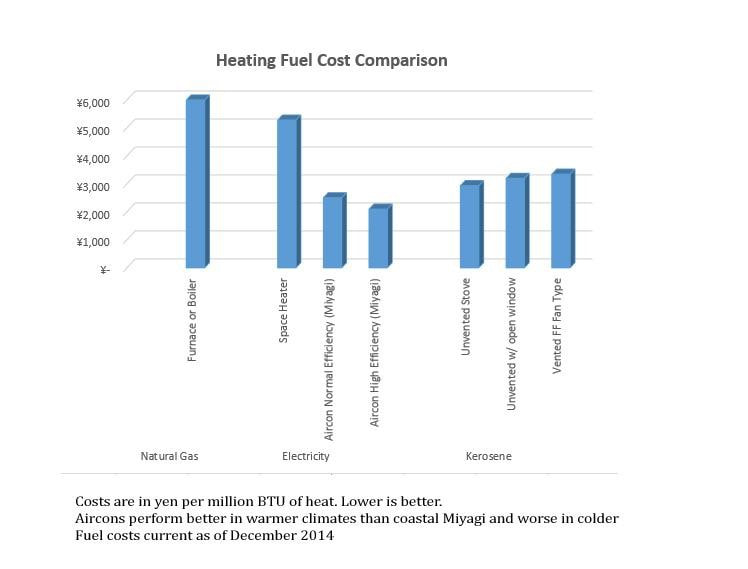

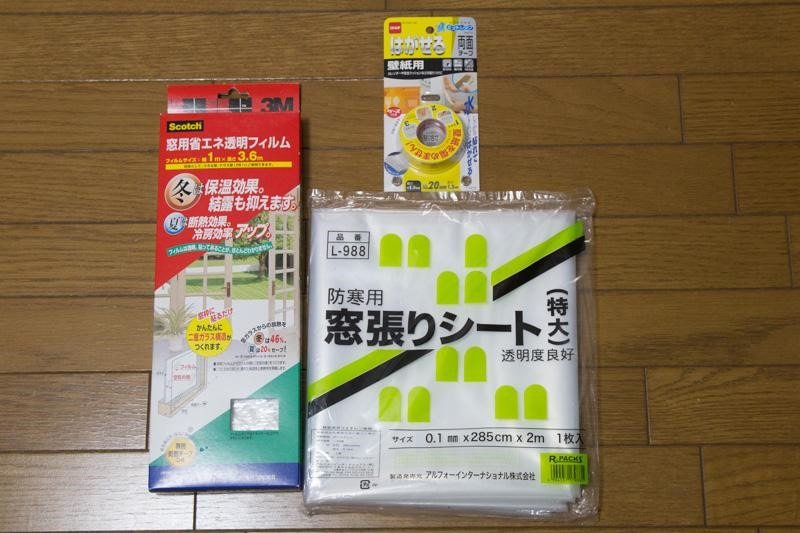

written by Roger Smith I. Japanese Homes 1. What to expect your first winter Japan has a point-heating approach to staying warm in the winter, meaning one or more rooms are kept warm by heaters located in those spaces. The rest of the living areas are allowed to get as cold as Mother Nature allows. Keeping warm is made far more challenging building standards that skimp on insulation even in modern and relatively efficient homes. A new state of the art home here has barely insulated walls that only perform as well as a double-paned window. The saving grace is that modern “mansion” apartments can be both small in size and fairly air tight, so even with minimal insulation it’s possible to heat them for a modest amount of money. 2. Mold and Moisture Most of Japan is humid and rainy, so homes are often designed with laminate flooring, metal windows, vinyl wallpaper and other materials that are water tolerant. The problem with this is that if water gets between spaces like floors and walls it may be unable to escape as these materials are vapor barriers. Trapped water that rots wood is part of the reason homes in Japan only last a few decades before being replaced. Japanese building practices further compound the problem as single-paned windows and underinsulated walls get quite cold in the winter. Anything that produces significant water vapor, such as use of an unvented kerosene stove, will result in water droplets collecting on these cold surfaces. If not removed manually, or prevented with a dehumidifier, this water can rot wood surfaces like window frames and provide a fertile growing area for mold, which can be a serious problem for people with asthma or allergies. Serious moisture problems even with careful use of exhaust fans and no stove heater II. Heating Systems: Pros, Cons & Costs 1. Unvented Kerosene Stoves Portable kerosene heaters known as oil stoves (石油 or sekiyu sutobuストーブ) though they generally use kerosene (灯油or touyu). These are still widely used in Japan, particularly in older homes. They are relatively cheap to buy, don’t require professional installation and efficiently convert fuel to heat. While the cost of kerosene has gone up dramatically in recent years, they are still overall affordable. Kerosene heaters with a battery backup can also be used in times of electrical blackouts. Kerosene heaters need to be refilled carefully and maintained properly to avoid spills and fires. The major downside of unvented kerosene heaters is that you are purposely releasing the exhaust gases into your living space rather than directing it outdoors. Burning any sort of fossil fuel indoors produces fine particles, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide and large amounts of water vapor. Dilution with outside air through an open window is necessary but not necessarily health-protective, especially for residents with allergies, asthma or other cardiovascular disorders. Continued exposure to low levels of carbon monoxide, beneath that which will trigger a CO alarm, are also associated with feelings of sickness and diminished mental performance. 2. Vented Kerosene Heaters While requiring professional installation, certain types of natural gas, propane, or kerosene space heater can be mounted on a wall with all the exhaust gases directed through a vent to the outside. Look for “FE” which is exhaust only ventilation, or better, “FF式石油ファンヒーター”which takes in combustion air from outside and returns exhaust outside. It is still important to have a carbon monoxide alarm in case the system fails, and a gas leak detector if using natural gas or propane. Expect to pay 50,000 to 150,000 yen for a modest size unit plus installation. 3. Electric Heaters Japan has many varieties of electric heaters, from oil-filled electric radiators to halogen heaters, heated carpets, heated kotatsu tables and more. Electric heaters produce no pollution or moisture, and require no installation as they can be placed anywhere there is an electrical outlet. They are all relatively affordable to buy (generally under 15,000 yen) and are equally efficient at converting electricity to heat. As electricity is an extremely expensive fuel, it is far more economical to use these heaters to heat people directly (as with a heated carpet), or to heat a small space (as with a kotatsu) than to use an oil heater to heat an entire room. 4. Aircon Heaters Known abroad as a “ductless mini-split heat pump,” Japan invented this form of heating decades ago. While known in Japan as air conditioners “aircon” (エアコン), most have reverse cycles that bring in heat in the winter. These units are powered by electricity but roughly three times more efficient than a traditional electric space heater as they use electricity to move heat between indoors and outdoors rather than to produce heat directly. Aircon consist of an outdoor unit that can be mounted on the ground, an outside wall, or placed on a roof or balcony, a hose to transfer coolant, and an indoor unit that mounts on an interior wall and circulates warm or cold air. They run on electricity and larger units need a 200V circuit. Note that they recirculate room air so you still need to ventilate the room with outdoor air in some way to reduce indoor pollution (24h換気扇 or always-on ventilation fan and 換気口 or air intake holes are standard in newer buildings.) Prices vary significantly by size (from 80,000 to 200,000 yen) and there are sales after the end of the summer cooling season and when new units are introduced at the start of the year. Expect to pay an additional 30,000 yen for a simple installation job and more if drilling new holes through walls is required. Not all aircon are suited for cold-climate use, but many modern ones are. Aircon are rated by the area they can heat in tatami mats (jo). It is important to choose one large enough to keep the room it will be located in at the desired temperature without running full-out. Unlike furnaces which alternate between off and putting out periodic blasts of hot air, heat pumps are most efficient putting out steady amounts of warm air and tapering off as the room gets up to temperature. Too large an aircon is better than too small. To compare units, look for higher APF efficiency numbers as well as the estimates for how much electricity it will use in a year (note that the standards assume it will run 18 hours a day year-round in Tokyo’s climate). As of early 2015, Fujitsu, Mitsubishi, Daikin and Panasonic advertise cold-climate models with information about its performance (significant heat output at -15C to -20C indicate cold climate units). For example, the 18-jo Fujitsu Nocria Z model claims 6.7KW (or 23,000 BTU per hour) of heat at 2C outside, which is well above the heat output of most kerosene heaters. 5. Heating Cost Comparison The only way to compare how much it costs to run different types of heaters is to see how much it will cost for each to produce the same amount of heat. This example uses winter 2014 electricity rates for Tohoku Electric, natural gas in Sendai, and kerosene costs. (Note: oil/kerosene prices have dropped a lot since 2014). Costs are in yen per million BTU of heat. The smaller the bar the cheaper. * Note that aircon perform better in warmer climates than coastal Miyagi and worse in colder City natural gas prices in Japan appear extremely high and not a cost-effective way of providing heat. The second most expensive heat source are standard electric space heaters. They are more than twice as expensive as any kerosene heater to produce the same amount of heat. Electric space heaters (ranging from kotatsu heated tables to stand-up units) can bring comfort to a small area but are very expensive if used to heat larger areas or left on for long amounts of time. Kerosene heaters are in the middle of the pack. Unvented kerosene stoves are slightly more efficient than vented units, as no heat is sent outside with the exhaust gases, but at the price of keeping all of the pollution and water vapor indoors. Determining the cost to run an aircon is more complex, as the performance and efficiency drops along with the temperature. In the cold climate of Miyagi Prefecture, unvented kerosene space heaters appear to cost a similar amount to run as a normal efficiency aircon. A cold-climate, high-efficiency aircon is likely the cheapest heating source to operate throughout most of Japan, which is why these are standard in new homes and businesses in Japan in all but the snowiest areas. This calculation only takes into account the cost of running each unit, and not the highly variable cost of purchasing and installing them. Savings from aircon may not, at current fuel prices, make up the cost to purchase and install them. On the other hand, aircon have none of the health and safety drawbacks of kerosene, and also provide air conditioning and dehumidification in the summer. Many apartments come equipped with them but residents assume they are expensive to run and choose not to use them in the winter. III. Tips for Surviving the Winter 1. How to Avoid Mold While less of an issue in winter than summer, mold growth can occur where there is excess moisture. Keep your apartment no greater than 45% relative humidity in the winter (lower is better) by always running an exhaust fan when cooking or showering, and minimizing or eliminating the use of unvented kerosene space heaters. Avoid the use of humidifiers if possible. Water vapor that condenses on cold windows, doors or other surfaces should be wiped up promptly and not allowed to penetrate into window frames, walls, and window ledges. Tatami rooms are susceptible to mold growth and beds or futons should not be left in contact with the mats. In addition they should be regularly vacuumed. Closets are also susceptible to mold growth and should be kept open to expose to air and light if possible. Mold can be killed and regrowth reduced by cleaning with a diluted white vinegar solution or a mixture of water and baking soda. Bleach is not recommended as it produces vapors that are harmful to health and can discolor surfaces. 2. How to Weatherize your Apartment An aftermarket industry exists in Japan to sell weatherization items to address the drafts, cold and condensation caused by low-performance windows, minimal insulation and leaky rooms. To solve the issue of window condensation it is necessary to prevent any warm, moist indoor air from contacting the cold window surface. The most effective way to do this is by covering the entire window opening with plastic sheeting affixed by removable tape to the wall or window trim. Choose tape appropriate for wood, vinyl or metal that can be removed without damage. This will effectively turn a single-paned window into a double-paned window. Note that this does reduce the amount of outside air entering the apartment and is not recommended in rooms where unvented kerosene heaters are used as the ability to dilute pollution by opening windows is very important.

Second best is affixing bubble wrap or other plastic sheeting to the surface of the window. This does not fix the issue of the metal window frame itself collecting condensation. Bubble wrap also reduces the amount of light entering the room and obscures the view of the outside. There are other work-arounds for window condensation, such as sprays which reduce the ability of water to condense on the surface, or foams which collect condensed water vapor, but none of these address the cause of the problem. For drafts, obvious gaps can be sealed with caulk, canned spray foam, or less permanently with stick-on foam strips. Heavy window drapes can improve comfort by reducing the feeling of cold coming from windows or sliding-glass doors. Other items like reflective foil mats and draft-blocking partitions that do not trap air likely do nothing to improve comfort or save energy (radiant barriers need to face air to work; cold air can easily go around a small partition.) 3. How to Run an Aircon Cheaply For almost every type of heater, the less time you operate it the less energy you use. That is why many Japanese people set their aircon to a high temperature (25C), run it full blast and then turn it off. Unfortunately that is the most expensive way to run an aircon. Aircon work most efficiently at less than their full power thanks to advanced electronics and inverter-driven variable-speed compressors. The best way to operate them is to set the remote to the desired temperature, set the fan speed to auto and let the unit run. Instead of forcing the unit to put out large amounts of heat at once, aircon work best by running for hours and continually topping off the amount of heat in the room. Note that if the aircon measures room temperature at the unit, you may need to set it several degrees higher to achieve that temperature in the farthest reaches of the room. Advanced aircon also have a temperature sensor in the remote control, which eliminates this problem if the remote is kept away from the aircon. The only time to turn off the aircon is if residents will be gone for many hours or longer, and during the shoulder seasons when much heat or air conditioning isn’t needed. Frequently changing the temperature on the aircon or turning it on and off will significantly increase energy usage. Disable “eco” temperature setback or auto-off occupancy sensing modes on the aircon. I recommend just keeping it on during the coldest months. Note that the efficiency of the aircon is highest when it is warm out, so if you do want to turn it off, consider setting the timer to turn it on in the mid-afternoon to get the room temperature back to comfortable levels instead of waiting until it is cold at night. Advanced aircon report the amount of electricity used per day so you can experiment with different settings and find the best balance of comfort and cost. For 100V units you can also connect it to a cheap electricity monitor to see how much electricity it uses and experiment by running it in different ways. Be sure to keep the aircon clear of snow or other debris that will restrict its ability to run. Do not pile items on or around the aircon. Periodically clean off the replacable aircon filter, or periodically empty the dustbin for aircon with auto-cleaning systems. Comments are closed.

|